ANCESTRAL TECHNOLOGY AND TIME CONSCIOUSNESS

We have no dedicated sense organ for the measurement of elapsed time, as we have for the measurement of vibrations in the air (forming sounds) with a wavelength and relative positions of light waves striking the retinas of our eyes. To speak of the ‘perception’ of time is to already speak metaphorically.

-Alfred Gell, The Anthropology of Time

Glowing portals, strange avatars, and alternate realities: are some of the promises offered by digital culture. Despite their modernity, these hyperlinked fantasies evoke traditions of primordial mythologies and rituals originating in Black and Indigenous epistemologies.

Similar to other forms of scholarship and culture, BIPOC people have not always received acknowledgment for contributing to the progression of the technology we interface with today. This act of erasure, while insidious, does however provide a substrate in which sustaining an identity in a world made of programs and pixels becomes possible. Indigenous peoples of the world might be said to have an upper hand in navigating the terrains of such indiscriminate territory.

Ancestral time is the mechanization of indigenous thinking that allows individuals to travel between pasts and futures occurring outside of human existence. The North American Hopi tribe believes that this slippage of time can be accessed through a ritual hole called the sipapu, which represents the point of emergence from other worlds into this one. This portal is a form of indigenous technology that illustrates the permeability between universes. A symptom of the digital landscape is that it has created new pools for us to enter. But, how do Black people conceive of a future when the future was never made for them? How does one disrupt linear time to reconcile the omission of existence to create a new spatial-temporal landscape? And to what extent is time measurable in the Black imaginary?

In Physics of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage Epistemology, Michelle M. Wright states that the “linear progress narrative to connect the African continent to Middle Passage Blacks today” creates a logical problem, because our timeline moves through geography chronologically, with enslavement taking place at the beginning, or the past, and the progression towards liberation moving through the ages toward the far right of a timeline, also representing the present.1

Timelines typically are arranged as a straight line, with significant dates plotting from the past, moving in one direction forward into the future. Time, for Black and Indigenous people, is liminal and open. It transcends Western concepts of linearity and empirical observation. It does not simply advance towards a conclusion or place. Time is a constant arrival and is meant to be transversed, played with, orbited, jumped into, sucked out of, and through. Within ancestral time cultures harness the ability to garner knowledge that lives beyond Western notions of logic and physics to create new ontologies and perceptions. Akin to the technology of remote sensing, ancestral time temporalities embody an ability to navigate across time zones and dimensions. The body is earthbound, while the faculties are untethered. Practices that impart ceremonial trance, systems of divination, or rituals with psychoactive plants, elicit out-of-body experiences where one may leave parts of their physical form behind to enter into the realms of guides, higher beings, past lives, otherworldly detritus, and sounds. Without making direct physical contact with the thing or place in question, one gleans and brings knowledge into their primary reality while also glitching history through mere survival and by taking up space in the future. Messages from other dimensions, ancestors, and the like are gifts from a place humans cannot inhabit. Time is never fixed. It becomes an undulating mirror for the spectator. It tints the future with a subtle hue of green, flesh, and hot silver flashes. Instinct. Intuitions. They all come flying towards you.

African Time

Indigenous African notions of time are usually experienced through backward linearity in that when events occur, they immediately begin their journey backward toward Zamani.2 In his work African Religions and Philosophy, Mbiti begins with an analysis of the African concept of time, believing that it is the key to understanding the African ontology, beliefs, practices, attitudes, and the general way of life of the African. Mbiti defines the African concept of time as “A composition of events which have occurred, those that are taking place now, and those which are immediately to occur.” 3

This division of time can be illustrated in potential time and actual time. Any time occurring outside of these two spaces is seen as no-time or non-time. Timelessness is a site of phenomenon. According to Mbiti, the actual time is what is present and what is past, revealing the African time as that which moves backward rather than forward. This would suggest that Africans set their minds on things that have passed rather than on the future and understand time as consisting of a long past and a present with virtually no future. For the African, the future is absent since it has not been realized. Many of the notations occurring in African time are the punctuation of event-centric thinking. Indigenous African notions of time are usually connected to natural events, such as moon phases, planting/harvesting seasons, rainy seasons, and other cyclical events that harness some sort of natural rhythm. Future events reside in potential time until experienced or actualized by the body. In contrast, the linear, Western concept of time consists of an indefinite past, the present, and the infinite future. For the African, the future is absent since it has not been realized. In some African languages like bamileke, there are up to eight different versions of the past tense.

Marooned Time

A very common saying in Jamaica is ‘soon come..,’ meaning sometime in the future. This gauge of time, however, can span anywhere between a few hours, days, months, or even years. While attempting to schedule meetings in Accompong with people or when I tried to figure out times when I needed to be present for the beginning of a drum procession or ceremony, I was always met with confusion from the villagers. They would respond with… “oh we will meet at sunrise,” or It will happen when it is supposed to happen. You will not be late. It is not possible for you to be late. It starts when you get there…”

Initially, I admittedly was irritated by this and it took some effort on my part to fall into this new experience of time. Once indoctrinated into the Maroon/Jamaican temporal sense of time, I entered into an unfamiliar sensation of time, which was timelessness. Although I was aware that beyond the town, life continued to live on, for some reason, I could not place this in my thoughts. I had begun to feel that I had fallen into a time warp and felt that I had been in the village for months, years…The comprehension of my life, family, university… everything became hazy and ceased to materialize in my mind’s eye. At moments this was very physically uncomfortable as I began to question my own spatial reality. It felt as if my body was beginning to leave, evaporate, and merge with the environment. The isolation of the bush played with my perception of what was actual, manifested, and false. Cloaked under the cover of the bush, this distortion of time grew stronger, while the physical separation from the outside world gave Accompong a sense of radical autonomy, allowing them to craft a unique version of liberation where their songs, rituals, language, and perception for the nonliving or nonhuman could be nurtured, taught and continued for generations to come. This constant returning to the past to frame a current, present state means that ancestors can never be left out of the equations of timefulness and experience. Here, Sankofa4 plays a significant role in how descendants of the Taino Maroons process their experience of knowing the world and how they place themselves in a future state. The dimensionality of marooned time was the substrate of their very livelihood and dedication to the land that their ancestors had won for them.

This absenteeism of time is a mutable process and acceptance of a void that can be redirected, re-orchestrated, played with, and constructed in the manner of one’s choosing. Having methods that intervene in the directionality of time means that Blackness exists outside of the perceived barriers of time’s unfolding, and allows us to become masters of it. Pathways of alternative relationships with other beings and realities become possible through embracing non-settler functions of time.

In her keynote address for Black Matter, Mpho Matsipa speaks about this liminal space and its offerings of rechanneling the dreams and wonders of possible Black futures:

“Black temporalities are promiscuous. precisely because the delay locates one in a liminal state of being which has transgressed and violated expected temporal boundaries. This form of temporal transgression of being out of time creates a shift in spatial and temporal coordinates that repeatedly disrupt linear time and hold open the possibility for reorganization, or manipulation of time and the enactment of diverse futures in the immediate present […] black time actually intensifies a deep sense of presence and the future simultaneously through aspirations hopes for a better future and needs to reconfigure current damnation. This temporality, this state of temporal suspension stretched, twisted to accommodate both imaginative failures and utopian moments that are enabled by desire.”5

As Kodwo Eshun writes in Further Considerations on Afrofuturism, “by creating temporal complications and anachronistic episodes that disturb the linear time of progress, Black futurist imaginaries adjust the temporal logics that condemned black subjects to prehistory.”6

To change the linear fatalistic future that Black people were told they did not belong to and to subscribe to their pasts beginning at the dawn of enslavement, Black people have had to actively and forcefully fight for space on the collective timeline. This concern of actual time, present time, and an absence of future time are important for understanding Black materializations of space and how this reality either problematizes or liberates a culture of thinking.

Blackspace and Utopic Visions

It is impossible to think about these two spheres of reality without confronting others, which are the real challenges that poverty, lack of quality healthcare and education play when Black people imagine a future for themselves and their descendants. Many global Black communities struggle to think about even a tomorrow that seems out of reach when you are concerned about basic human amenities and rights. These social and economic barriers to the future place Blackspace in perpetual a state of presentism.

Guerrilla theorist and curator, Neema Githere takes ownership of this sanctioned time by naming it Afropresetism. Githere notes that Afropresentism is the ability to channel one’s ancestry through every technology at our disposal—meditation, conversation, love, the internet —and to transform everything into a portal that takes the Black body precisely where it should and needs to, in this moment, towards the next, until the space between the dream and memory collapses into being a complete reality—now. Not to be confused with Afrofuturist thinking, she clarifies its distinction by stating that Afrofuturism is concerned with space, while afropresetism is concerned with Earth and does not situate the future as an escapist utopic vision, but claims space boldly and unapologetically in the present.7

“Afropresentism, this indigenous technology of connection and love, informs everything about how I move around the world, the things I take notice of, and what I do with them.”

- Neema Githere

While afropresetism is centered on how to navigate our digitally soaked psyches, Tricia Hersey, founder of Nap Ministry is calling for a full pause for Black bodies altogether. Through performance art, site-specific installations, and community organizing, Hersey invites communities of color to trade the capitalist desire for productivity hacks, keeping busy and burning the midnight oil, simply for the fact that our bodies and the bodies of our ancestors have been forced to endure labor for the sake of society’s gain for centuries. Through rest, and napping workshops, she hopes that her work will offer marginalized communities respite and resistance. The work of NapMinistry, I would argue, is a form of petit-marronage, or short-term flights and absenteeism from the demands of Europatriachal power structures, and becomes part of one’s daily survival ritual.

When thinking about gleaming utopias and their convenient refusal to work through racism, sexism, class, gender, poverty, and other discriminatory realities, how does blackspace witness a future? Utopias are untroubled, unbothered regions that occupy no real space in time or reality. In contrast, heterotopias agitate the status quo of experience, subsequently holding up a mirror to the fissures in our society and forcing us to take notice. H. G. Wells describes these heterotopias as “disturbing,” and “destructive” to the syntax of speech, allowing them to dissolve myths and sterilize the lyricism of our sentences.8

Ancestral time plays up this severance in that the heterotopia’s are enlivened by halting the expectations of an optimal destination, or endpoint deep into the future. This ruptured space must be inspected, practiced, and disseminated widely throughout the culture, for only out of this disquieting disruption will society submerge itself in its shortcomings to emerge with alternative epistemologies and visionings that bring marginalized bodies into future worlds.

The temporalities of waiting—such as those used by the maroons and the purposeful withdrawal from Western time’s comprehension and use of time as a servant of production and value, provide Black rituals, languages, and knowledge the opportunity to flourish while opening pathways for collaborations with other nonhuman entities, systems, and biota on an individual and collective scale. Ancestral time-consciousness unsettles the normalizing sanctions of power that seek to destroy blackspace and is a strategy of resistance and the preservation and production of Black knowledge.

Wright, Michelle M M. Physics of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage Epistemology. N.p., University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

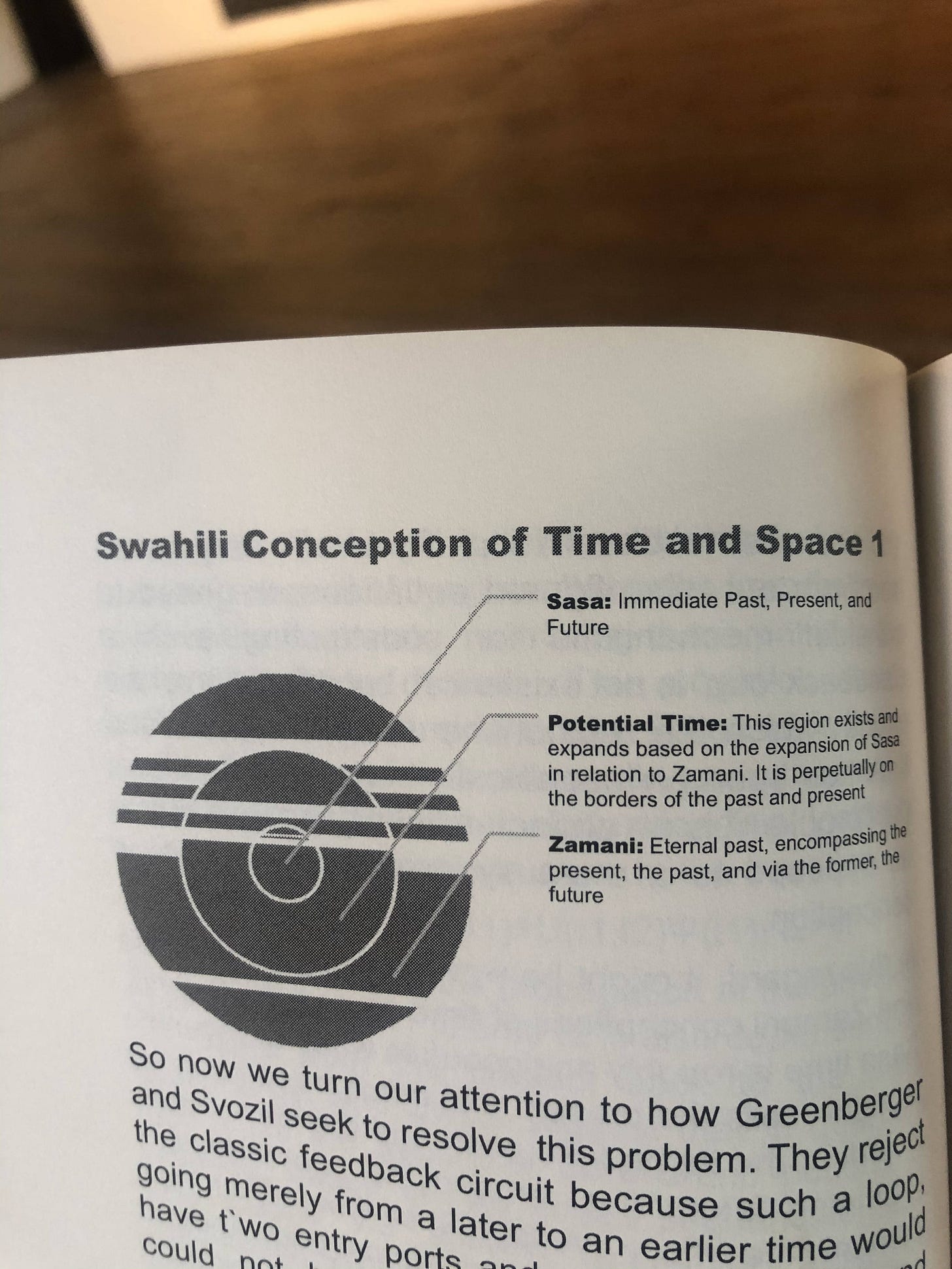

Zamani is not limited to the past. It also has its own “past, “present,” and “future,” but on a wider scale. Zamani might be called Macro-Time (Big Time). Zamani overlaps with Sasa [the Micro-Time] and the two are not separable.

Mbiti, John S.. African Religions & Philosophy. United Kingdom, Pearson Education, 1990. Pg. 17

Sankofa is an African word from the Akan tribe in Ghana. The literal translation of the word and the symbol is “it is not taboo to fetch what is at risk of being left behind.” It expresses the importance of reaching back to knowledge gained in the past and bringing it into the present to make positive progress. This includes knowledge and experiences of ancestors from generations past. Within my Ifa community, it was emphasized that we must fulfill the duty of filling out as much of our family tree as possible, and work diligently to research to trace our lineage. Through divination and dreams, the lived experiences of ancestors often come through. It is also believed that the traumas of our ancestors can themselves in our bodies through pain or illness. Similar claims have since been verified through contemporary biology and the encoding of trauma in our DNA.

Matsipa, Mpho. “Black in Design 2021: ‘Black Matter,’ Keynote Address by Mpho Matsipa.” YouTube, uploaded by Harvard Graduate School of Design African American Student Union, 25 Oct. 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=u6Sm7SLcQkU&list=PLqxr4aBubkPbKo8wClHh2SSDq1mvmgDg3&index=1.

Eshun, Kodwo. “Further Considerations of Afrofuturism.” CR: The New Centennial Review, vol. 3, no. 2, 2003, pp. 287–302. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1353/ncr.2003.0021.

“On Afropresentism.” Neema, www.presentism2020.com/on-afropresentism. Accessed 1 June 2022.

Wells, Herbert George. Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress Upon Human Life and Thought. Germany, Chapman & Hall, 1902.